The early morning fog engulfed my car as I came around a curve on the river-bluff highway one hour into the trip. I braked and crept along, afraid I would crash into a car ahead of me or be hit from behind. I clenched the steering wheel and wondered if I made a mistake turning down a friend’s offer to drive me. I was determined to make the ninety-minute drive from Minneapolis to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota alone. For once I didn’t say no to them from my automatic self-sufficiency reflex. This seemed like a sacred journey to me. I needed to be alone. It was likely I would hear for a second time that the metastatic brain tumors, which refused to respond to radiation or chemotherapy, could not be surgically removed. The Minneapolis neuro-oncologist told me the Mayo doctors would say the same thing. I came anyway. I was already facing death from the cancer, and now powerlessness over this tumor and the possibility of losing my mind. I knew I must have silence and time for reflection after this appointment to come to grips with this new stage of my cancer journey. It was too big to talk about.

I glanced over at the passenger seat and saw that my tote bag had fallen to the floor when I slammed on the brakes. Medical records, discs with images of my brain and body, and a pile of forms I spent hours filling out the night before spilled out. I wished I had someone sitting in that the empty seat right now.

Then, as quickly as it appeared, the fog was gone. The morning sun burned it off, revealing blue sky and sunshine. I got to the clinic in no time after that, but I was still shaken from that fog.

I stuffed everything back in the bag, and struggled out of the car with it. I knew from experience that when I was this tired, I could easily forget where I parked. I pulled out my phone and took a snapshot of the parking ramp door as I exited. A maintenance man working nearby said, “Bravo! What a great idea. Everyone should do that.” I replied, “Well, I’ve got a brain tumor and that’s why I’m here. I don’t trust my brain much today. He said, “They will take good care of you here. I wish you all the best.”

I felt a slight spring in my step after that compliment, and maybe even a bit smarter as I followed the signs leading me towards the Gonda Building. This seemingly endless tunnel was carpeted and quiet. I appreciated not having to hear the sound of clicking heels rushing past me in both directions. Private nooks tucked in along the way held a love seat, dark brown wooden end tables and lamps with bronze bases and creamy linen shades. Seeing them reassured me that I could stop and rest comfortably between the ramp and building if I needed to. Calm surrounded me as I walked.

Next, I entered a wood-paneled hall covered with Andy Warhol prints of endangered species. I never knew he did this series and stopped to read about them. I still had my phone out from the ramp picture, so I clicked some pictures of them. Their bright and bold colors cheered me on. I felt a bit like an endangered species myself.

When I entered the Gonda Building lobby, my destination, my heart started to race. I stopped right where I was, took several deep breaths trying to relax and gather energy at the same time. Why did I make this trip anyway? What if they said the same thing? Inoperable. Would I need whole-brain radiation that would take away my cognitive ability? My research showed average prognosis of just months after whole brain radiation for metastatic tumors. Would I just let the tumor grow, which could cause blindness and then death? Would I even have a choice? I wanted to bargain and trade any other part of my body to take this tumor instead of my brain. Wide-awake now from the racing mind and heart, I was forty-five minutes early and wondered what to do next.

On my left, through floor-to-ceiling windows, I saw a mass of tulips and pansies, and a row of simple wooden tables and chairs. I stepped outside and the sun warmed my face while I walked along the flowerbeds. These were the first outdoor flowers I had seen after a particularly long and harsh winter.

I realized I was smiling. I took a dozen photos trying to capture the colors and the simple beauty of this outdoor space. I stayed out there until it was time to meet the neuro-oncologist. One more deep breath and I stepped inside. I walked up to the information desk. (Photo below from the web.)

Directly across from the desk was a gigantic painting called “Home.” It was done in Pointillism style. I was stunned, because I had just used Pointillism in a short talk at a legal symposium, a gathering of innovative legal minds and practitioners from around the world, committed to improving the profession of family law and the courts. A linear, chronological model for the talk just wouldn’t have worked for my story. Neither would bullet points. Pointillism came to me at the last minute, a remnant of my college degree in French. I decided I would describe the most important moments from my work and life, putting them up one by one, on an imaginary canvas, like dabs of paint. I trusted this would create the true portrait of my life and work when I was finished speaking, even if it wasn’t immediately clear how it all connected. I wanted others to feel free to bring all parts of themselves forward too, even if they weren’t sure yet how they connected to the symposium. The reception to my talk was favorable.

How often does one think of Pointillism, much less use it in a talk about the legal system? Then see a form of it again a week later in a hospital? I stood there in awe about the synchronicity we occasionally get to experience in life. I knew in my heart this was a momentous day and this confirmed it. On the spot, I decided to continue taking photos as I took this journey into the unknown.

It was time to go up to my appointment.

Every time the elevator door opened on the way up to the eighth floor, I caught a glimpse of well-lit museum quality glass cases, holding art objects such as jewelry, ancient mosaics, and sculptures. The art lover in me wanted to jump right off and get a closer look but I continued on to my appointment, hoping to return afterwards for a better look if I could enjoy it after the appointment.

The eighth floor lobby seemed more like a library to me than a medical clinic: wood tables, computer stations, reading lamps, leather chairs, natural light, and outlets for charging electronic devices.

The only “clinical” looking thing I saw so far was the entrance door and hallway to the neuro-oncologist’s office. The woman at the counter said I would be called in through that door. It had a ” B” over it and definitely looked like a medical clinic inside. I said, “Well, at least I’ll remember B for brain tumor —I use mnemonic devices since I’m having some troubles with memory.”

Laughing, she said, “There you go! You’ll always know which door to go through today!”

The clerk gave me a pager so I could keep roaming. Instead, I sank into a soft leather chair by the windows and put the heavy tote bag on the floor. I noticed I was excited to be here at the Mayo for the first time and looking forward to meeting this new expert. It was worth those weeks of chasing around Minneapolis with multiple release forms to get all my medical records together. It was worth the drive through the fog. I knew now that my life was worth a second look, even though the neuro-oncologist in Minneapolis said they would just tell me the same thing. It was ok for me to want to try to extend my precious time.

Just then a young man called me into the “B” door and got my height, weight and blood pressure in less than a minute or two, as we stood just inside. Then he brought me into an office and waved me to a chair. He said, “Have a seat. The doctor will be right in.” I sat down to wait for the person I came to see. No intervening nurses, no delays, no bureaucracy, no having to tell my story for the umpteenth time.

The doctor had a large framed print of an ocean shore. I noticed he had many small thank you cards pinned to his bulletin board. Other than that it was minimalist and exceedingly clean.

The neuro-oncologist came right in. Within the first few minutes he immediately took away the horrific label “inoperable brain tumor.” He had already scheduled an appointment for me with a brain surgeon at three o’clock that afternoon. My whole body relaxed into the chair.

He used the metaphor of a chess board to describe my situation. He said, “I am teaching my daughter to play chess. I showed her how you can’t touch a piece without moving it. First you think about all the choices you can make. That’s what we will be doing here.” Having played chess, I understood what he meant. Looking at your next move from all different angles, anticipating the move the other player might make in response, as far ahead as possible before moving, was an apt metaphor for the talk we were about to have.

I was riveted by his clear and intelligent explanation of what he saw as my options and his reasoning behind them. Yet I couldn’t help but interrupt him at one point. “Why, when my cancer-filled bones have been stable with hormone therapy for two years, why would some of these cells break away and go to my head? Why didn’t they respond to the hormone therapy like the all the other cancer cells?”

He looked me in the eye and said, “You just tapped into a cutting-edge question in cancer research.” This surprised and pleased me. My brain was not gone yet. I may not have followed exactly what he said there, but my understanding is that the cancer not only has to break off from another tumor, travel through the bloodstream, get through the highly protective blood-brain barrier (which most chemotherapies cannot even penetrate) then set up and grow in a completely new habitat. Yet it is one of the most common sites for metastasis in some cancers and the prognosis is usually grim. I recall him saying cancer researchers were working hard on trying to figure this out.

We concluded with a clear plan of action and then he handed me the name of the brain surgeon I would be seeing in three hours.

I left his office feeling good. I went out for a walk, a cup of tea and a light lunch at a nearby cafe. After a few sips of tea I was drawn right back to the Gonda Building. I had no interest in shopping, walking or sitting outside even though it turned into a perfect spring day.

When I entered the Gonda lobby this time, there was a young woman in the center playing the ukulele, singing “Hey, Soul Sister.” A crowd gathered—medical people in blue or white coats, families with young children, a few folks in wheelchairs. The second story balcony was filled all around too. Tears filled my eyes as I looked around at the diversity of those who gathered around her, patients and doctors, the sick and the well. I took a video of the room and the singer. When she was done she said, “I’m sorry I won’t be here next Tuesday. I will miss you all. I just graduated from medical school and will be moving.” A doctor playing a ukulele and singing every Tuesday in the Mayo Clinic lobby. Another surprise.

When she finished to a round of applause, I took an escalator to view the array of 13 handblown, whimsical chandeliers designed by Dale Chihuly, the world-renowned glass blower. I read on the description that he’d been injured in a car accident and although he designed these, others had to execute the design due to his injuries.

Imagine 13 variations of this gigantic sculpture over your head as you come up the escalator. You start on the ground floor, and can see them all lined up above you. As you ascend, you get closer and closer to them. I had to hang on tightly to the escalator handrail out of fear I might fall backwards. I couldn’t take my eyes off them.

On the sign at the top of the escalator, I read that Chihuly left it untitled. His only goal was “to make people feel good.” He knew what it was like to have an injury or illness and be left unable to live your life the way you once did. That did not stop him from creating. Feelings of inspiration and connection flowed through to me from reading this after seeing the fantastic creations. These were beyond anything I had ever seen in a gallery.

At the end of the description it said: “This piece emphasizes the Mayo Clinic’s commitment to the vital role art plays in the healing process.”

I spent a half-hour with those chandeliers and took dozens of photos. Then my cell phone rang. The surgeon could see me right then, rather than in three hours.

My appointment with the surgeon went well. He could not get it all but he could get the main part. It could be analyzed. Maybe there was something we would learn from that to help us understand it. I felt complete as I exited the door marked “B” for the last time. I had extra time now and went back to the elevator to view the art pieces I saw on the way up. Ancient jewelry and mosaics were my favorites.

I reflected on the day’s unexpected beauty. I realized there was no magic answer or cure for me at the Mayo Clinic. I still had the brain tumor and a terminal diagnosis. Their surgeon couldn’t get it all, but he would operate if I wanted. It might help, it might not.

At the end of a Commonweal cancer retreat I attended in 2005 in Bolinas California, co-founder Michael Lerner said something I never forgot. He told us, “You may not find a cure for your cancer, but you can still find healing.” Through my journey to the Mayo, I came a little closer to understanding what that means.

I brought my fear and despair on the journey, that was clear. The Mayo Clinic’s art, music and garden engaged more than just the terrified and grieving cancer patient who first showed up. Mayo welcomed all of me that day—art lover, musician, lawyer, wife, mother. My sorrow and imperfections were fully present as I appreciated spring tulips, Warhol, Chihuly and Soul Sister. When everything is allowed, we experience what many call integration, or more simply, what I call peace—peace with life just as it is. No amount of research, logic, or even a cure for the cancer could have given me this gift.

Late afternoon shadows fell on the Gonda Lobby as I crossed over it for the last time to head for home.

Afterword-

I did not undergo the partial surgery at Mayo. I stayed on the chemo for close to another year, and continued to struggle with severe fatigue. It was like I walked away from the chessgame midstream, unable to make a move. Or maybe, without realizing it, I was waiting for something better to come along.

It did.

It is a story of mysteries and miracles.

Miracle

I wish each and every one of you could experience the joys of receiving an abundance of loving messages like those I have been receiving in my guestbook on Caring Bridge but without having to go through a major health challenge.

(Maybe we could start something like that.)

I have switched to posting on Caring Bridge https://www.caringbridge.org

This is because of the the variety of medical experiences I have had the past few years. I was hesitant to do this, putting all this personal information online, but realized how loved ones might worry about me if I didn’t. All those misgivings are gone now, because so many kind people are on the caring bridge with me. Thank you.

This is the story of how a mystery, or a miracle, guided me to the next move to take care of the brain tumor

For close to a year after they found the braintumor, I suffered exhaustion, whether from the radiation, chemotherapy, or the cancer itself. Nothing made a dent in it.

Despite being tired, I made a special effort to attend parent-teacher conferences for my twins even though I had no concerns about their schoolwork. I wanted to make a connection with their arts high school before they graduated. I missed many school activities because of my brain tumor.

I carefully chose just three teachers I would meet with.

I looked forward to my last conference with visual arts teacher Pat Benincasa. She is an accomplished artist, teacher, and a creative force who inspired my son Tom to find his artistic voice, confidence, and motivation. He often told me how she guides the student artists with personal attention and encourages them without criticism. In addition to teaching, she helped him select his portfolio for college applications. He was accepted into his first choice art school with a generous talent scholarship. When he relayed their personal conversations or summarized her talks to the class, he spoke about her with what I might call reverence.

No other parents were waiting in line, so I joined her in a quiet corner with comfortable chairs. I started with my gratitude for her mentorship of my son. Being a supportive parent is important, but it does not compare to the impact of receiving personal encouragement from an objective and accomplished artist.

I was drawn to her immediately and began to share personal stories, like the brain tumor. I talked about how committed I was to guiding my three boys with love and authenticity in whatever time I had left. Our conversation became like an improvisational duet of joyful, kindred spirits. We talked about the power of art, creativity, and kindness to uplift and heal. We talked about the challenge of bringing these values into institutional systems like education, law and medicine. We talked about how healing and beauty can arise out of suffering, pain and hardship. It was exhilarating to be in her presence. I left with a heart filled with gratitude and a smile on my face.

The next day, I pulled into the school parking lot to pick up Tom. He was waiting outside for me at the curb waving a manila envelope.

“Mom! Pat Benincasa gave this to me to give to you. It must be really important because she asked me five times during the day if I had it and to be sure to give it to you tonight. Can I watch you open it?”

He jumped in the car. I parked and said he could open it for me. He ripped it open, and inside we found a handwritten letter to me and a small envelope printed with the words, “Joan of Arc Scroll Medal.” As he read her letter out loud, we both started crying. She wrote she had been thinking about our conversation, and how she found me amazing for so many reasons.

Pat said that in 2006 she created this engraved St. Joan of Arc Medal for servicewomen and men to wear on their dog tags, and since then, over 5,300 have gone out worldwide. She wrote, “I also started to send the medal to all people I read about—and who I realized were ‘People of Courage’—you are one of them.”

The page of recipients she included with the medal listed my name beside the first woman president of Harvard, the Boston Police officers who responded to the marathon bombing and others of that caliber. After my name she wrote, “For her continuous and tireless legal, civic, and public engagement to speak for the disenfranchised, voiceless and marginalized people. Her passion to make a difference has made that difference in the lives of young and old everywhere.”

We were speechless.

I took the medal out of the packet held it.

If I were to pick a patron saint for myself, (something I would never have considered doing before receiving this medal) I now believe it would be Joan of Arc. I majored in French and loved France so much I wanted to live there, but my mother was in a wheelchair suffering from MS and depended on me as her caregiver so I came home.

After I received the medal I did some quick research on Joan of Arc, and learned that this seventeen year old woman warrior followed her deepest calling, even when it seemed impossible, even after she was wounded. Joan was a peasant girl who couldn’t read or write. At age seventeen, she left home to convince the crown prince Charles that she received a divine message to lead the French army to Orléans and take it back from the English. She promised she would prevail and then see him crowned king of France.

Joan of Arc endured ridicule and doubt. An illiterate young girl with no military experience seeking to lead France’s military—it was absurd. She held firm in her mission and her faith until she succeeded in meeting with Charles. Against the advice of his generals and counselors, Charles gave her an army and put her in charge. She succeeded, just as she had predicted. Later she was captured by the enemy and Charles did nothing to rescue her. After a corrupt trial she was burned at the stake. She never once wavered from her faith even in the time of her death.

During our meeting, I never told Pat my love of France. I didn’t tell her about surviving a childhood of abuse, neglect and poverty, or how I lost my voice before I was five years old, with what I later learned was ‘selective mutism.’ I was clearly an unlikely candidate to become a lawyer, judge or leader. Yet I kept going, and did accomplish these things in my quiet way.

I had to quit working in the courts when the cancer returned. Although my bones were stable on hormones, rogue cancer cells went to my brain. The local surgeons refused to operate. A Mayo Clinic surgeon said he would, but he likely couldn’t get it all.

I told Pat during our conference, that I just had an article published in an international journal which I called, “Putting a Heart into the Body of Law” — an article about my life’s mission to improve the legal system and make it one based on kindness, care and respect. I told her how difficult it was when I tried to bring change based on those values to the family court. I had bureaucratic doors slammed in my face many times, but I kept going. I would joke and say I tried to “make a dent in the universe,” (borrowing Steve Jobs’ phrase,) but I ended up with a dent in my forehead instead. It was a dream come true to finally be able to share my values and visions with the world through the international journal. (The full article can be found by clicking on LOVE. )

I rushed to a local craft store for a chain to put on the Joan of Arc Medal. I took a long time finding exactly the right one. Then several attempts by the clerk to cut it to precisely the right length. I took up a lot of her time, so when she was ringing me up, I began to explain why this medal was so important to me. I had some tears when I mentioned the inoperable brain tumor, my three teen-aged boys, and the artist and teacher who gave this to me.

The clerk dropped everything and started clicking at her computer, then spun it around to face me. It was the website for the Barrows Neurological Clinic with a photo of Dr. Robert F. Spetzler.

She said, “My best friend had an inoperable brain stem tumor that she was told was terminal by four surgeons. This doctor in Phoenix took it all out. Later, it grew back on the other side of her brain stem and he took that out too. She is a mother of three also, and has been cancer free since. He saved her life.”

Her friend, still cancer free, had over 100,000 visitors to her caring bridge site, and was writing a book. She had just completed a Triathalon.

I called Barrows, flew there in February with all my records and met with Dr. Spetzler. He said he would absolutely try to get it all. He thought he could. He was humble and extremely kind to me. When I read about him I was flabbergasted at his massive accomplishments and creation of techniques that changed the world of brain surgery forever. I was in the presence of greatness, but he acted like I was the only important person in the room.

I scheduled the surgery for his first open date—March 12. I hesitated a moment before saying yes, because this was the date my mother died, when I had just turned 24. It was also the date I became a mother, sixteen years later. Now this.

Dr. Spetzler completely removed that tumor.

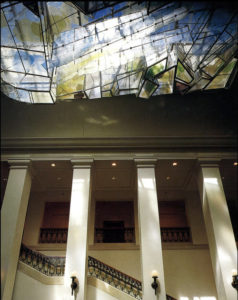

There is yet another miracle. I discovered for the first time, when I looked up the artist Pat Benincasa’s website gallery, that she won a national competition in 1995 to create and install her seven-ton glass and steel skylight entitled Falling Water Skylight, for The Grand Stair Hall of the Minnesota Judicial Center on the State Capitol Grounds in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Pat Benincasa has made much more than a dent in the universe. She created an opening in it. An opening of beauty, where light and healing can enter a place that truly needs it.

May my good news, positive results, and brush with mysteries and miracles give hope to those who suffer from this disease. May the light of mystery and miracles shine on you always, healing your challenges and illuminating your joys.

Below: Falling Water Skylight and Joan of Arc Scroll Medal, by Artist Pat Benincasa.